Inside the Sharded Model:

3-D Parallelism

Part 3 of Jaxformer (Part 2: Base Model | Part 4: Dataset & Config)

Here we discuss the 4 main parallelism techniques used for scaling LLMs: data parallelism, fully-sharded data parallelism (FSDP), pipeline parallelism and tensor parallelism. For each, we discuss their theory and a scalable implementation.

Foundations of Sharding

When scaling models in JAX, we need to explicitly control how the data and computations are partitioned. This is where the intuition behind manual parallelism techniques in JAX comes in.

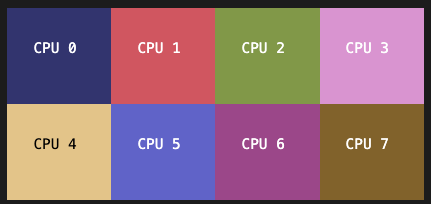

To begin, the environment can be set-up to simulate an arbitrary number of CPU devices, here 8 are being simulated. Note that all XLA flags must come before JAX imports because the flags are parsed once. This means they need to be defined in the environment before importing JAX to ensure they are recognized.

import os

os.environ["XLA_FLAGS"] = '--xla_force_host_platform_device_count=8'

from functools import partial

import jax

import jax.numpy as jnp

from jax.sharding import Mesh, PartitionSpec as P

from jax.debug import visualize_array_sharding

from jax.sharding import NamedSharding

from jax.experimental.shard_map import shard_map

The configuration of these devices can be shown by calling jax.devices() which returns:

[CpuDevice(id=0),

CpuDevice(id=1),

CpuDevice(id=2),

CpuDevice(id=3),

CpuDevice(id=4),

CpuDevice(id=5),

CpuDevice(id=6),

CpuDevice(id=7)]

Mesh and Shard Map

Before explicitly sharding tensors across devices, we can create a jax.sharding.Mesh to define a grid of available devices, reshaping them into custom configurations and assigning a name to their axes. This allows for multi-dimension sharding along the defined axes (for example, data parallelism along one axis and pipeline parallelism on the other). In this case, since we have simulated 8 devices, they have been split into a $2 \times 4$ configuration along the x and y axes respectively (note the names are arbitrary, x represents the axis with 2 devices and y represents the axis with 4 devices).

mesh = jax.make_mesh((2,4), ('x', 'y'))

Now, to demonstrate sharded vector addition across 8 distinct devices, we can begin allocating two vectors a and b, which are reshaped to be of the same configuration as the device grid and an element-wise addition function to be called on each individual device.

a = jnp.arange(8).reshape(2,4)

b = jnp.arange(8).reshape(2,4)

def vec_addition(a, b):

return a + b

Then, to call the function of each of the 8 devices, we can use jax.shard_map which maps a function over arrays distributed across devices. Shard_add is defined as a wrapper around the shard_map that maps the function vec_addition defined as element-wise addition, on the 2 x 4 device mesh, where each of the arguments to vec_addition(a, b) are split across the x and y axes, whilst the output is also split on each of the devices. This is represented by the partition spec object P() which specifies how the input and outputs should be partitioned across the devices.

shard_add = jax.shard_map(

vec_addition,

mesh=mesh,

in_specs=(P('x', 'y'), P('x', 'y')),

out_specs=P('x', 'y'),

)

c = shard_add(a, b)

visualize_array_sharding(c)

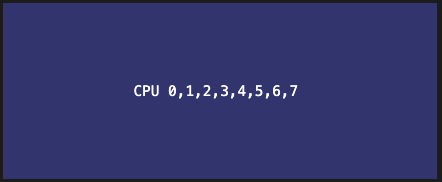

Using visualize_array_sharding(c), we can see how the sum is split-element wise on each of the devices.

When printing the values of vectors a, b and c, we see that the element wise addition worked.

Array([[0, 1, 2, 3], [4, 5, 6, 7]], dtype=int32) #a

Array([[0, 1, 2, 3], [4, 5, 6, 7]], dtype=int32) #b

Array([[ 0, 2, 4, 6], [ 8, 10, 12, 14]], dtype=int32) #c

Replication with All-Gather

In the case where the whole vector c should be replicated across the devices, the following changes would need to be made. In the device-wise vector addition function, each device does element wise addition on its shard. Then, the first all_gather, along the mesh axis x concatenates the results along dimension 0 of the array. This results in each device along the same column with the same data, essentially collecting all elements column-wise. Then, the same is done row-wise along the y axis/dimension 1. The final local result is an array of shape (2,4), essentially replicated across each device. So, the shard_map function on the bottom, calls the vec_addition function on each device which does local addition, then all gathers all elements for each device in the mesh defined above. The input vectors a and b are sharded across all the devices; however, the output remains P() because it means the output is replicated on all devices, instead of staying sharded. Then, the argument check_vma=False is passed. VMA is JAX’s sharding verifier; however, it cannot infer the result of certain operations, i.e the all-gather has replicated the arrays fully. Thus, turning it off allows us to write unchecked shardings which we know are correct.

def vec_addition(a, b):

local_result = a + b

local_result = jax.lax.all_gather(local_result, axis_name="x", tiled=True, axis=0)

local_result = jax.lax.all_gather(local_result, axis_name="y", tiled=True, axis=1)

return local_result

shard_add = shard_map(

vec_addition,

mesh=mesh,

in_specs=(P('x', 'y'), P('x', 'y')),

out_specs=P(),

check_vma=False

)

c = shard_add(a, b)

visualize_array_sharding(c)

When visualizing the output, the following is shown where c remains the same sum as above. It shows that c is replicated the same across all devices.

That concludes an introduction to distributed training in JAX. These principles are then scaled across higher-dimensional arrays to form the basis of modern distributed techniques including data, pipeline and tensor parallelism.

Data Parallelism

Gradient Averaging

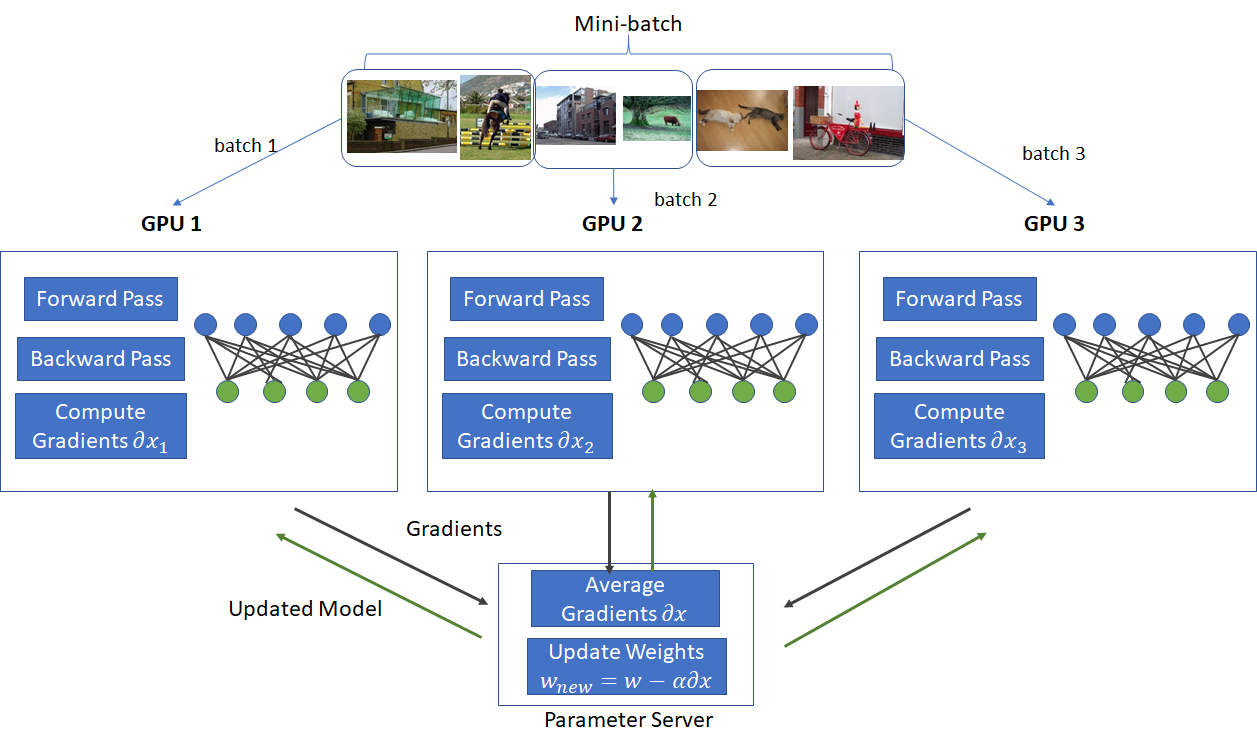

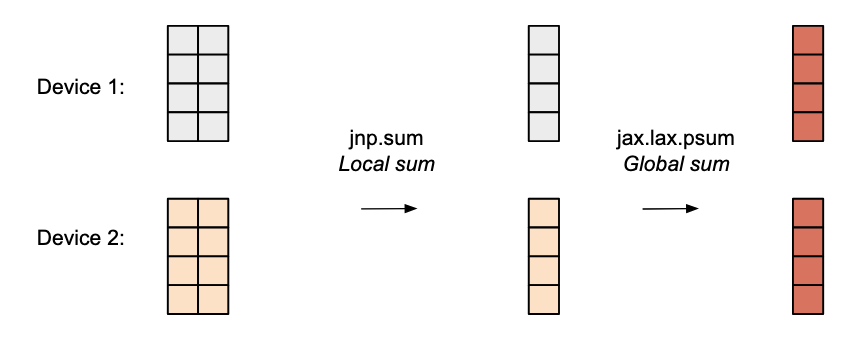

There exist numerous parallelism strategies (data, tensor, pipeline) for training large language models. Data parallelism, as the name suggests, involves replicating the model across compute whilst parallelizing the data. At its core, data parallelism splits the batch size of the input shape (B, T, C) into smaller batches that are distributed across n devices (B/n, T, C). In this way, we can increase the batch size as each device processes a subset of the data independently, in parallel. After computing the forward pass and obtaining the gradients, they are averaged across all the devices, using the jax.lax.pmean(x, axis_name)operation and updated across every model. Since the weights are replicated (have partition spec of P()) JAX automatically does a gradient sync. This operation, performs an all-reduce mean on x along the axis_name in the grid mesh of devices and thus the gradients will sync when jax.grad is called.

def loss_fn(...):

loss = ...

loss = jax.lax.pmean(loss, axis_name='dp') # reduce across data parallel

return loss

The advantages of data parallelism allow for large-scale training with low communication bottlenecks as there is only one communication required. One of the main disadvantages of it is that the model is required to fit on each device, this can be infeasible as the model grows, hence data parallelism is often combined with other strategies including pipeline and tensor parallelism.

Fully-Sharded Data Parallelism

Pure data parallelism doesn’t require changes in our model class. However, the biggest downside of data parallelism is that the model needs to be replicated in each instance. This leads to large memory usage. A way to fix this is to use an extension of DP known as Fully-Sharded Data Parallelism, where each model keeps a subset of the parameters and performs all-gathers to ensure that only a single instance of the parameters are replicated. The same goes for the gradients and optimizer states. To implement this, we only need to ensure the parameters are sharded since our gradients and optimizer state are as computed and sharded in the same partition spec as the parameters they represent.

We implement FSDP on the weight matrix for the dense network only. Since every dense layer is wrapped in our own class, this is reasonable for parameter sharding. We begin by writing the Dense module ourselves in terms of Flax Linen parameters instead of using the class given by Flax. We initialize a kernel which is our weights matrix and a bias. Then, we cast to the desired data type, perform a matrix multiplication and add the bias.

class Dense(nn.Module):

features: int

dtype: jnp.dtype = jnp.float32

@nn.compact

def __call__(self, x: Array) -> Array:

kernel = self.param(

"kernel",

nn.initializers.lecun_normal(),

(x.shape[-1], self.features),

jnp.float32,

)

bias = self.param(

"bias",

nn.initializers.zeros,

(self.features,),

jnp.float32

)

x, kernel, bias = jax.tree.map(

lambda x: x.astype(self.dtype), (x, kernel, bias)

)

x = jnp.einsum("...d,df->...f", x, kernel) + bias

return x

For FSDP initialization, it is acceptable to replicate parameters across each sub-axis (both pipeline and tensor), since inference would not be possible otherwise, as FSDP is not used during inference. However, after initialization, we need to all-gather the kernel. This can be done by using self.is_mutable_collection("params") to determine what stage we are at. If we are in the initialization (params are mutable), we can initialize the kernel normally, otherwise since Flax manages the parameters of an nn.Module, we can collect the current kernel in the scope of the function and all gather it. For the all gather, we want to do it across the data parallel axis abbreviated in our mesh as dp along the last dim of the matrix and we want to concat them not stack them so we pass Tiled=True.

def __call__(self, x: Array) -> Array:

if self.is_mutable_collection("params"):

kernel = self.param(

"kernel",

nn.initializers.lecun_normal(),

(x.shape[-1], self.features),

jnp.float32,

)

else:

kernel = self.scope.get_variable("params", "kernel")

kernel = jax.lax.all_gather(kernel, "dp", axis=-1, tiled=True)

There are a few unanswered questions left, such as how do we split the parameters after they are made, or how do we prevent JAX from storing the activations in memory for the backward pass (which eliminates the benefits of FSDP). These will be answered below but, assuming we are able to spilt the parameters (each kernel) across the dp axis (x.shape[-1], self.features / dp.size), we are able to perform the desired FSDP operation. The rest of the Dense class remains the same for now (Tensor Parallelism requires further operations). Therefore our Dense is:

class Dense(nn.Module):

features: int

dtype: jnp.dtype = jnp.float32

@nn.compact

def __call__(self, x: Array) -> Array:

if self.is_mutable_collection("params"):

kernel = self.param(

"kernel",

nn.initializers.lecun_normal(),

(x.shape[-1], self.features),

jnp.float32,

)

else:

kernel = self.scope.get_variable("params", "kernel")

kernel = jax.lax.all_gather(kernel, "dp", axis=-1, tiled=True)

bias = self.param(

"bias",

nn.initializers.zeros,

(self.features,),

jnp.float32

)

x, kernel, bias = jax.tree.map(

lambda x: x.astype(self.dtype), (x, kernel, bias)

)

x = jnp.einsum("...d,df->...f", x, kernel) + bias

return x

Pipeline Parallelism

Naive Pipeline and GPipe

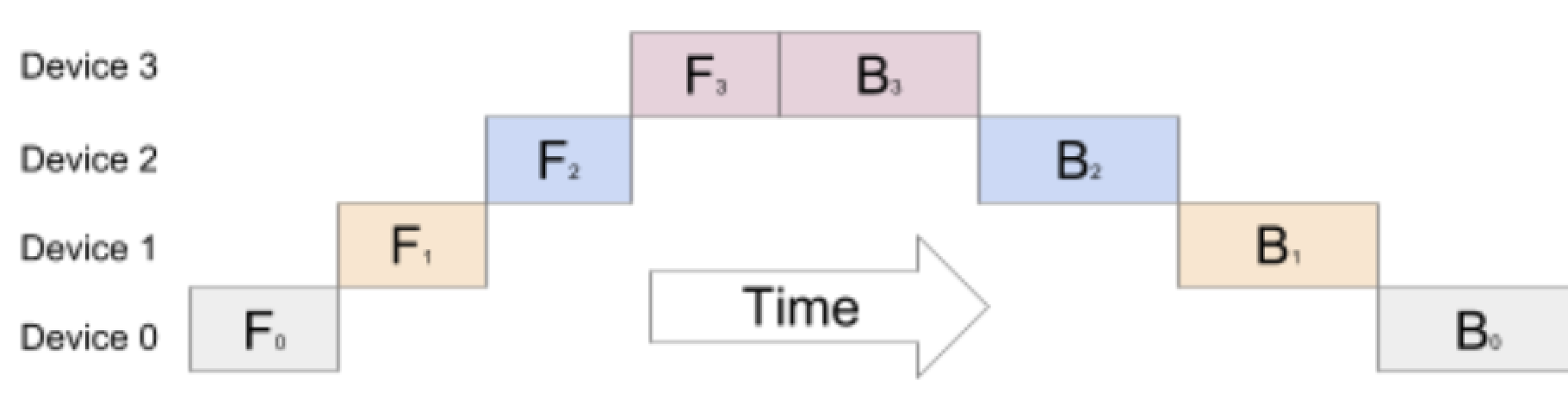

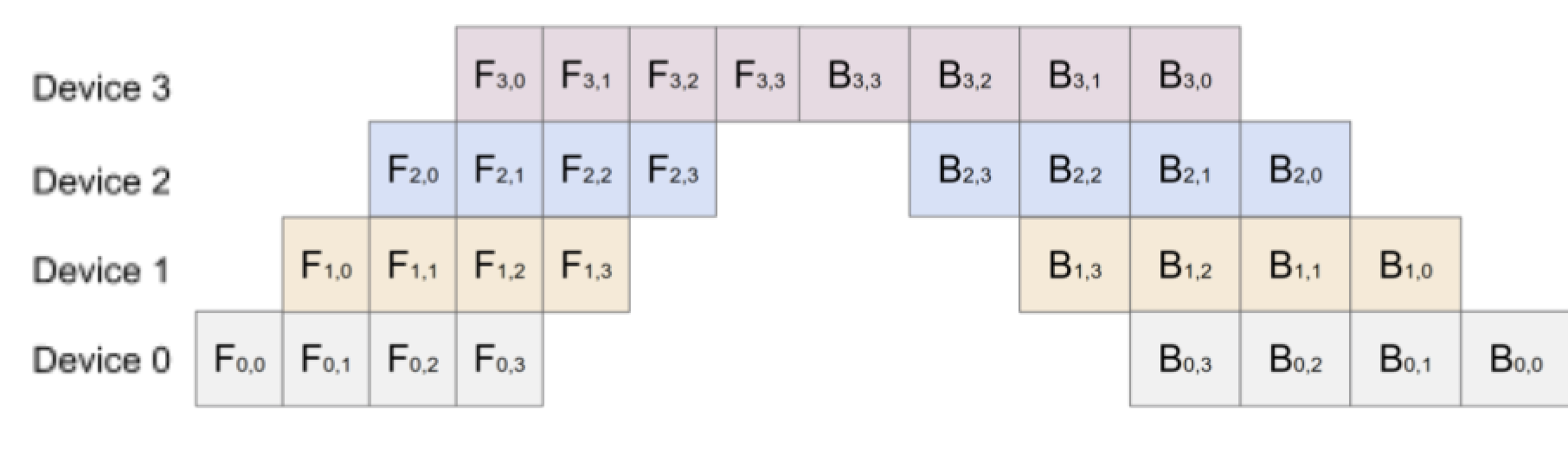

Pipeline parallelism is another parallelism technique that allows for training LLMs across distributed nodes. While data parallelism works well for smaller to intermediate models, when the model size increases, it becomes difficult to scale as the model can no longer fit on a single device. Hence, in such cases, strategies that parallelize the model instead of the data need to be used. In pipeline parallelism, the model is split vertically. This means the layers of the model are partitioned on different devices, for example, a transformer with 16 layers and 4 homogenous devices are split evenly (4 consecutive layers per device). The input batch passes through the first device with the first n layers, then the output of that device is passed to the next device through the next n layers and etc. The backwards pass is formed in the opposite direction from the last device, computing the gradient for the last n layers, then computing the back propagation through the next device and etc. Pipeline Parallelism is advantageous because each device requires a portion of the model, allowing for more scaling as memory requirements are reduced. Due to the nature of this parallelism, the following computation graph can be created.

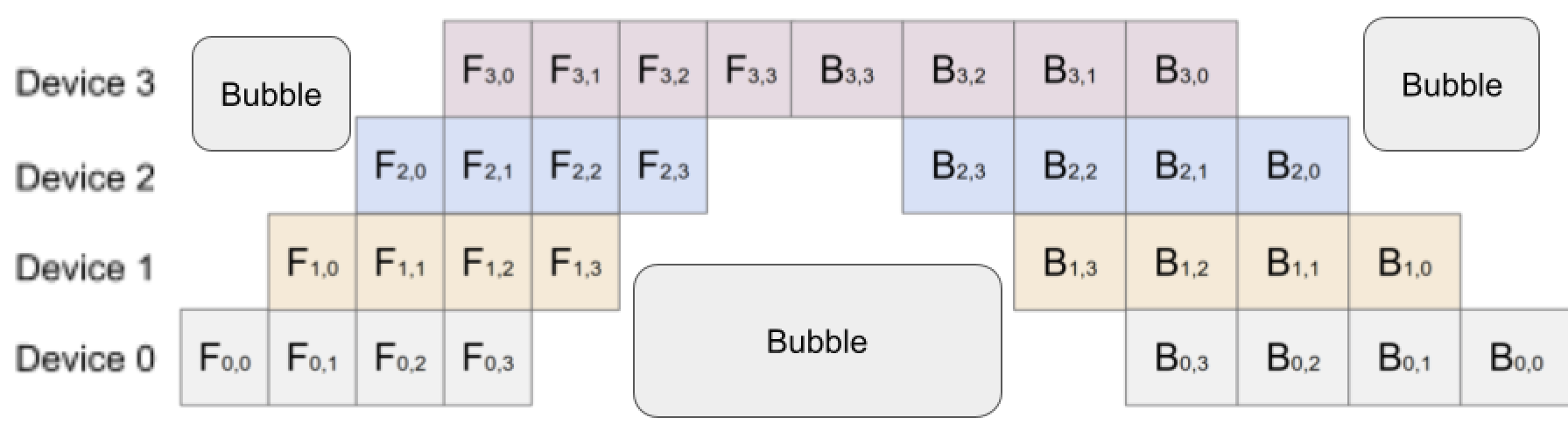

Looking at the figure, it is evident that the forward pass of each state is dependent on the device before it and as a result, in the image above, the devices are idle for a large amount of time. This causes an low underutilization of devices as at any time step, only one device is being used. Hence, the GPipe Algorithm was introduced to increase device efficiency by splitting the batch size into mini batches (smaller, equal-sized batches) for which the forwards and backwards pass can be computed sequentially. Now, each device can immediately start working on the next micro-batch and can be overlapped over each partition. The idle time of the device is called a bubble, which can be reduced by choosing a smaller size of micro-batches.

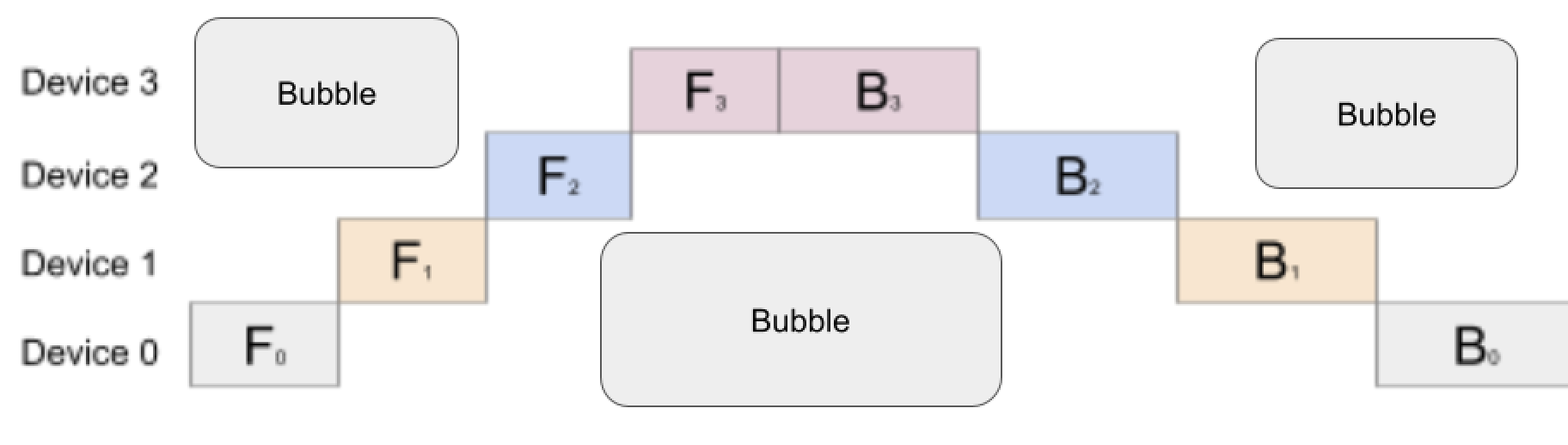

When looking at the fraction of time wasted by the bubble, the formula can be derived looking at the following image for naive pipeline parallelism.

To calculate the portion of time as a bubble, assume $n$ to be the number of devices. Then, the amount of idle time for the top left bubble can be calculated as the arithmetic sum between 1 and n-1.

\[\frac{(n-1+1)(n-1)}{2} = \frac{n^2 - n}{2} = \frac{n(n-1)}{2}\]The top right bubble is calculated as twice the top left bubble, as the magnitude of time the backwards pass takes is twice that of the forwards pass. Hence, the top left bubble is $n(n-1)$. It is trivial to prove that the center bubbles are equal to the sum of the top left and top right bubbles, hence the final bubbles sum can be computed as:

\[2\frac{n(n-1)}{2} + 2n(n-1) = n(n-1) + 2n(n-1) = 3n(n-1)\]The numerator of this ratio has been computed above; however, the denominator is computed as the total amount of time taken by all the devices. This ratio can be computed as $n(n + 2n) = 3n^2$. Thus, the ratio of time wasted in the naive pipeline is:

\[\frac{3n(n-1)}{3n^2} = \frac{(n-1)}{n}\]It is evident that as n gets larger, the fraction of time wasted approaches 1, signifying heavy inefficiencies. Computing this ratio for the GPipe Algorithm yields the following.

To calculate the total bubble ratio, we can use the same procedure as above to calculate the total bubble time as:

\[2\frac{n(n-1)}{2} + 2n(n-1) = n(n-1) + 2n(n-1) = 3n(n-1)\]The total time taken is equivalent to the total area which is $n * 3(n+m-1)$ since in each forward pass, we have to do $n+m-1$ passes and twice that in the backwards pass. When dividing the two, we get:

\[\frac{3n(n-1)}{3n(n +m-1)} = \frac{n-1}{n+m-1}\]Note that when $m = 1$, this equation becomes the same equation above. So, increasing the size of the mini batches, results in a smaller ratio of bubble-time wasted; however, we cannot infinitely increase the mini batch size because that will result in an underutilization of the GPUs and increase in communication costs, so we must maintain a balance between the two. GPipe papers have that when $m \geq 4n$, the communication cost becomes negligible.

Parameter Partitioning for Pipeline

There are two main challenges when implementing pipeline. The first is the actual forward/backward pass and the second is setting up the parameters. We begin by setting up the parameters.

Currently, our parameters are represented as a JAX PyTree (any Python data structure such as a list, tuple, or dictionary whose children are JAX arrays), specifically as a dictionary where the module keys serve as paths. For example if we want the first down block for the MLA, we can do params['Block_0']['Layer_0']['MLA_0']['Dense_0'] = {'kernel': Array(...), 'bias': Array(...)}. Now when we have a PyTree and use sharding functions (i.e jax.device_put) it maps over the tree hence if p is some PyTree, jax.device_put(p, NamedSharding(...)) = jax.tree.map(lambda x: jax.device_put(x, NamedSharding(...)), p). This leads to a problem with the current Transformer class since it’s parameters are sequential, meaning it may have keys Block_0, Block_1, … Block_n where we want to shard the first n/pp_size blocks on the first device, then the blocks from n/pp_size + 1, 2n/pp_size on the second device and so on. One way to fix this and make it more natural in JAX is to consider partitioning only across the Blocks. Then since each of the params in Block_0, Block_1, … ,Block_n are identical (they all have the layers defined), we can create the parameter dictionary as one block with all the parameters stacked. This allows the parameters to be sharded across the pipeline axis. Instead of having params = {'Block_0': {...}, ..., 'Block_n': {...}}, we now have params = {'Block_0': {...}}, where each block includes a leading axis. For example, instead of a kernel having the shape (4, 8), it now has the shape (L, 4, 8), where L is the number of layers in the model.

To begin writing this out, we can create a new class called ShardedModel which will be used to implement all the sharded features. In the constructor, we can split the embedding and block into two separate components since we will want to manipulate the parameters of the block independent of the embedding module.

class shardedModel:

def __init__(self, cfg: modelConfig):

self.dtype = convert_dtype(cfg.model_dtype)

self.embedding = Embedding(

vocab_size=cfg.vocab_size,

model_dimension=cfg.model_dimension,

model_dtype=self.dtype,

)

self.block = Block(

layers=cfg.layers_per_block,

model_dimension=cfg.model_dimension,

n_heads=cfg.n_head,

T=cfg.T,

latent_dim=cfg.latent_dim,

dhR=cfg.dhR,

dropout_rate=cfg.dropout_rate,

model_dtype=self.dtype,

)

self.cfg = cfg

Before we can write the initialization method for the weights, we need to have some function that inputs the config of the model and returns a Partition Spec of the parameters. This will allow us to write the init method under a shard map, allowing for direct creation on devices rather then transfer which would defeat the whole purpose of using parallelism methods.

To do this efficiently, we use the jax.eval_shape function, which returns the shapes of a function’s outputs. Since we do not care about the actual values, only the dimensions, we can use these shapes to construct the final PyTree structure and the PartitionSpec.

The function first takes a few variables that are needed to make the mock data such as the sequence length T, the number of layers and number of devices. It then sets up the mock data and a key needed for the init methods which generate the fake parameters (again fake because we aren’t actually going to use these parameters it just tells us the structure we are working with).

class shardedModel:

...

@staticmethod

def get_p_spec(

model: Tuple[Embedding, Block], mesh: jax.sharding.Mesh, config: modelConfig

) -> Tuple[jax.sharding.NamedSharding, jax.sharding.NamedSharding]:

T = config.T

n_devices = mesh.devices.shape[1]

n_layers = config.blocks

assert n_layers % n_devices == 0, (

"Number of layers must be divisible by number of devices"

)

embed, layer = model

x_embed = jnp.ones((1, T), dtype=jnp.int32)

x_layer = jnp.ones((1, T, embed.model_dimension), dtype=jnp.float32)

key = jax.random.PRNGKey(0)

Then, we write a function that eval_shape can call to generate the fake parameters. This function is placed under a shard_map since we want to replicate the stacked structure. Note that for the out spec, we replicate the embedding params on every device and the layer we concatenate on the pipeline axis. This differs from the real output of the model since some of the parameters such as the kernels of any dense layer are also split in the FSDP style. We first init the embed module normally. Then, we make n_layer // n_devices of the layer module and stack each array in this PyTree onto one dim. This way, when we concat on the pp axis, we are able to get the parameters aligned on one dimension which will be sharded in pipeline parallelism.

@staticmethod

def get_p_spec(...):

...

@partial(

jax.shard_map,

mesh=mesh,

in_specs=(P(None, None), P(None, None, None)),

out_specs=(P(), P("pp")),

)

def get_var_spec_shard(x_embed, x_layer):

embed_shape = embed.init(key, x_embed)["params"]

layer_shape = []

for _ in range(n_layers // n_devices):

layer_shape.append(layer.init(key, x_layer, train=False)["params"])

layer_shape = jax.tree.map(lambda *x: jnp.stack(x, axis=0), *layer_shape)

return embed_shape, layer_shape

eval_shape = jax.eval_shape(

get_var_spec_shard,

x_embed,

x_layer,

)

We can now use jax.tree.map to go through the shapes and convert them to the desired PartitionSpec. If we are in a layer parameter, we want to split everything on the first axis across the pp axis but only the kernels (which are 3 dim) along the dp axis since we perform the all-gather to collect the params in FSDP. We keep explicit representations for gamma/beta since for future parallelism like tensor, we will need to revisit these rules. Embeddings will be replicated on each device for now since we only need to split the the block across the pipeline axis.

@staticmethod

def get_p_spec(...):

join_fn = lambda path: " ".join(i.key for i in path).lower()

def layer_partition(key: Tuple[str, ...], x: Array) -> P:

path = join_fn(key)

if "gamma" in path or "beta" in path:

return P("pp", None, None, None)

if x.ndim == 3:

return P("pp", None, "dp")

return P("pp", None)

embed_p_spec = jax.tree.map(

lambda x: P(

*(None for _ in range(x.ndim)),

),

eval_shape[0],

)

layer_p_spec = jax.tree.map_with_path(

layer_partition,

eval_shape[1],

)

return embed_p_spec, layer_p_spec

Forward Pass and GPipe Execution

We can now begin writing the init_weights method. It will follow in similar structure to the get_p_spec function. We begin by getting the out_spec. Then, we will replace the dp axes in any of the layer partition with None for now since in initialization, we don’t want to split the Dense kernel’s across the dp axis.

class shardedModel:

def init_weights(self, key, mesh):

out_spec = shardedModel.get_p_spec([self.embedding, self.block], mesh, self.cfg)

def replace_fsdp(p: jax.sharding.PartitionSpec):

if p[-1] == "dp":

p = P(*p[:-1], None) # remove None from last position

return p

out_spec_no_fsdp = jax.tree.map(lambda x: replace_fsdp(x), out_spec)

We can then prepare our init variables, namely our mock data and unique keys for each layer to ensure that each layer being created is not an identical copy.

def init_weights(...):

...

x_embed = jnp.ones((1, self.cfg.T), dtype=jnp.int32)

x_layer = jnp.ones((1, self.cfg.T, self.cfg.model_dimension), dtype=self.dtype)

layer_devices = mesh.devices.shape[1]

assert self.cfg.blocks // layer_devices, "Number of blocks must be divisible by number of devices"

layers_per_device = self.cfg.blocks // layer_devices

key, embed_key = jax.random.split(key, 2)

key, *layer_keys = jax.random.split(key, layer_devices + 1)

layer_keys = jnp.array(layer_keys).reshape(layer_devices, 2) # make into jax array

We can now write out sub-function init_params identical to sub function in the get_p_spec only now using different keys.

def init_weights(...):

...

@jax.jit

@partial(

jax.shard_map,

mesh=mesh,

in_specs=(P(None, None), P(None, None, None), P("pp")),

out_specs=out_spec_no_fsdp,

)

def init_params(x_embed, x_layer, layer_key):

layer_key = layer_key.reshape(2)

embedding_params = self.embedding.init(

embed_key,

x_embed,

out=False

)["params"]

layer_params = []

for _ in range(layers_per_device):

layer_key, init_key = jax.random.split(layer_key)

current_params = self.block.init(init_key, x_layer, train=False)[

"params"

]

layer_params.append(current_params)

layer_params = jax.tree.map(

lambda *x: jnp.stack(x, axis=0),

*layer_params

)

return embedding_params, layer_params

We can call this to get back our variables and use device_put to move them to the Partition Spec with FSDP.

def init_weights(...):

out_spec = shardedModel.get_p_spec([self.embedding, self.block], mesh, self.cfg)

...

out_spec_no_fsdp = jax.tree.map(lambda x: replace_fsdp(x), out_spec)

...

@jax.jit

@partial(

jax.shard_map,

mesh=mesh,

in_specs=(P(None, None), P(None, None, None), P("pp")),

out_specs=out_spec_no_fsdp,

)

def init_params(x_embed, x_layer, layer_key):

...

return embedding_params, layer_params

params = init_params(x_embed, x_layer, layer_keys)

params = jax.tree.map(

lambda x, y: jax.device_put(x, jax.sharding.NamedSharding(mesh, y)),

params,

out_spec,

)

return params

Now, we can move on to the actual forward pass for the pipeline implementation. We’ll call this step pipe_step, and it will take the same arguments as a standard model.apply(...) call. We begin by unpacking the parameters (since they are provided as a tuple) and if the cache is not None taking the last token in x similar to what we did in the Transformer class. We can then apply the self.embeddings module like a normal JAX module.

For now, we’ll comment out the pipeline implementation for the layers by treating it as a black box and assuming the embeddings output is passed through it. We can then reapply self.embedding without=True to obtain the final logits.

def pipe_step(self, params, x, key, train, cache=None):

embedding_params, layer_params = params

if cache is not None:

x = x[..., :1]

embeddings = self.embedding.apply({"params": embedding_params}, x, out=False)

# some pipeline implmentation here

# embeddings become layer_out

logits = self.embedding.apply({"params": embedding_params}, layer_out, out=True)

return logits, cache

So far this is identical to the transformer. We now turn our attention to the actual pipeline implementation.

We start by writing a forward function that passes through a single batch through self.block.

def pipe_step(...):

embedding_params, layer_params = params

if cache is not None:

x = x[..., :1]

embeddings = self.embedding.apply({"params": embedding_params}, x, out=False)

layer_fn = lambda x, params, cache, key: self.block.apply(

{"params": params},

x,

cache=cache,

train=train,

rngs={"dropout": key} if train else None,

)

...

return logits, cache

There are a few downsides of such a simple layer function. The first is we can speed up implementation if we know we do not have to compute the gradient for some pipeline stages, namely the stages in the bubble. Below we will see that the stage is originally made with nan values hence we can write a wrapper on this function to choose between a stop-gradient method if there is a nan, otherwise call this layer function. Specially we can keep a state_idx which will be written below that indexes into the array for which function should be used. We can also remat (a.k.a checkpoint) this function to save memory since we are training on TPU’s whose individual HBM are quite low (< 30GB).

def pipe_step(...):

layer_fn = lambda x, params, cache, key: self.block.apply(

{"params": params},

x,

cache=cache,

train=train,

rngs={"dropout": key} if train else None,

)

@partial(jax.checkpoint, policy=jax.checkpoint_policies.nothing_saveable)

def fwd_fn(state_idx, x, params, cache, key):

def grad_fn(stop_grad):

return (

lambda *args: jax.lax.stop_gradient(layer_fn(*args))

if stop_grad

else layer_fn(*args)

)

fns = [

grad_fn(stop_grad=True),

grad_fn(stop_grad=False),

]

return jax.lax.switch(

state_idx,

fns,

x,

params,

cache,

key,

)

We can now write the function that will execute the GPipe phase, which we will call pipeline. This function takes the forward function to be executed at each stage (our layer_fn from the previous code block). The stage_params are the stacked parameters for the local layers on the device. For example, if we have $L$ layers and $n$ devices, the leading dimension of each parameter’s shape is $L/n$. Concretely, a kernel with input size 4 and output size 8, with $L = 10$ and $n = 2$, would have stage_params of shape (5, 4, 8). The inputs are the local inputs arranged into microbatches per device. If $x \in \text{dataset}$ has a global shape (M, B, T), where $M$ is the total number of microbatches, $B$ is the batch size per microbatch, and $T$ is the sequence length, then under the pipeline (since it runs inside a shard_map), the shape becomes (M / pp_size, ...) because each device processes an equal share of the total microbatches. The cache corresponds to the KV-cache at each stage and the key is the main JAX key for the specific device.

def pipeline(

self,

fn,

stage_params: PyTree,

inputs: Array,

cache: Optional[Tuple[Array, Optional[Array]]],

key: jax.random.PRNGKey,

):

# implementation goes here

return logits, out_cache

The first step is to get all the variables needed to define our pipeline loop. That is we need

def pipeline(...):

device_idx = jax.lax.axis_index("pp") # current device in pp axis

n_devices = jax.lax.axis_size("pp") # total devices

layers_per_device = stage_params["Layer_0"]["MLA_0"]["Dense_0"]["kernel"].shape[

0

] # layers per device

layers = layers_per_device * n_devices # total layers

microbatch_per_device = inputs.shape[0] # microbatch per device

microbatches = n_devices * microbatch_per_device # total microbatches

We can then create our outputs with the same shape as the inputs and our state, which is a buffer of the input/output for all the layers on the current device (this will be used to send data to different devices). Additionally, we create the mask matrix for states that are carrying nan values and the permutation that we will use a bit later. The permutation is just an array of tuples with increment values to indicate which pairs of devices will communicate (each device will communicate with its neighbour in the given arrangement). We also make the arrays for the KV-cache identical to the Transformer class.

def pipeline(...):

...

outputs = jnp.zeros_like(inputs) * jnp.nan

state = (

jnp.zeros(

(

layers_per_device,

*inputs.shape[1:],

)

)

* jnp.nan

)

state_idx = jnp.zeros((layers_per_device,), dtype=jnp.int32)

perm = [(i, (i + 1) % n_devices) for i in range(n_devices)]

KV_cache = []

KR_cache = []

As explained above, the total number of steps in the forward pass is n + m - 1 where $n$ is the number of devices , $m$ is the total microbatches. However this is a simplification, as the true number of steps is $L + m - 1$ where $L$ is the total number of layers since we now have to consider if there is more then 1 layer per device. In each stage we have to do 3 steps. The first is to load the correct data and prepare the arguments (KV-cache, etc.), the next is to actually call the forward function and the next is to communicate the data. The first variable is batch_idx, which indicates the current microbatch being processed by the device. For each interval of microbatch_per_device, the device uses its local inputs, after which it rotates to obtain the next batch from another device. After we have gone through all the microbatches (i > microbatches - 1), the batch_idx becomes meaningless (we have reached the stage where the first device no longer is providing useful outputs). Similarly the layer_idx tells us which index of the output we are on. It only becomes useful after $i > L - 2$ since that is when the first microbatch has passed through the last layer. After we have completed microbatches_per_device steps, we rotate the output to start filling it for the next device’s microbatches. After we have computed both indexes, we set the state’s 0 index if we are on the first device for pipeline (essentially the device that holds the first layer) and set it equal to the batch_idx of the input, otherwise we keep the current state value. Similarly we set the state_idx’s 0 index at the 0 device to be 1 indicating it is no longer filled with nan values. We also make enough keys for the layers on this device for the forward computation and if the cache is not None, we make a tuple of the cache values.

def pipeline(...):

...

for i in range(microbatches + layers - 1):

batch_idx = i % microbatch_per_device

layer_idx = (i - layers + 1) % microbatch_per_device

state = state.at[0].set(jnp.where(device_idx == 0, inputs[batch_idx], state[0]))

state_idx = state_idx.at[0].set(jnp.where(device_idx == 0, 1, state_idx[0]))

key, *layer_keys = jax.random.split(key, layers_per_device + 1)

layer_keys = jnp.array(layer_keys)

current_cache = None

if cache is not None:

current_cache = [cache[0][i], None]

if cache[1] is not None:

current_cache[1] = cache[1][i]

We can now use the jax.vmap function to use vectorize the forward pass for the layers on this device. The function to vectorize over is the function given as a parameter and we pass in all the variables we have prepared. This now becomes our new state and cache.

def pipeline(...):

...

for i in range(microbatches + layers - 1):

...

state, out_cache = jax.vmap(fn)(

state_idx, state, stage_params, current_cache, layer_keys

)

We are now on the final step which is to prepare the outputs. We append the out cache again identical to the Tranformer class and set the outputs at the layer_idx to the last state if this is the last device since that is the last layer.

def pipeline(...):

...

for i in range(microbatches + layers - 1):

...

if out_cache[0] is not None:

KV_cache.append(out_cache[0])

if out_cache[1] is not None:

KR_cache.append(out_cache[1])

outputs = outputs.at[layer_idx].set(

jnp.where(device_idx == n_devices - 1, state[-1], outputs[layer_idx])

)

We now need to rotate the state values across the pipeline devices. To achieve this, we use the jax.lax.ppermute communication operation, which sends a JAX array along a specified axis according to a given permutation. Specifically, we permute the last index of the state along the pp axis using the defined permutation and then prepend it to the front of the state. This is because we are collecting the last state from the previous device, which must now be passed into the first layer. The remaining state values stay the same but are shifted down by one. The same procedure is applied to state_idx, since it serves as a mask over the state values

def pipeline(...):

...

for i in range(microbatches + layers - 1):

...

if out_cache[0] is not None:

KV_cache.append(out_cache[0])

if out_cache[1] is not None:

KR_cache.append(out_cache[1])

outputs = outputs.at[layer_idx].set(

jnp.where(device_idx == n_devices - 1, state[-1], outputs[layer_idx])

)

state = jnp.concat(

[jax.lax.ppermute(state[-1], "pp", perm)[None, ...], state[:-1]],

axis=0

)

state_idx = jnp.concat(

[

jax.lax.ppermute(state_idx[-1], "pp", perm)[None, ...],

state_idx[:-1],

],

axis=0,

)

The other two arrays that may need to be shifted are the inputs and the outputs. If batch_idx has reached the last microbatch, i.e., batch_idx == microbatch_per_device - 1, we must also permute the inputs to fetch a fresh batch. Similarly, for the outputs, when we reach microbatch_per_device - 1, we rotate to begin filling the next device buffer. For the inputs, it is important to note that once $i > M - 1$, no further rotation is needed, since all inputs have already been processed. For the outputs, although we are continuously filling and permuting the array, it only becomes relevant once $i > L - 2$, because at $L - 1$, the first batch reaches the final output and starts populating the output array. From $L - 1$ onward, we must step $M$ more times, which ensures that each device fills its output array exactly once.

def pipeline(...):

...

for i in range(microbatches + layers - 1):

...

if batch_idx == microbatch_per_device - 1:

inputs = jax.lax.ppermute(inputs, axis_name="pp", perm=perm)

if layer_idx == microbatch_per_device - 1:

outputs = jax.lax.ppermute(outputs, axis_name="pp", perm=perm)

With that we are done the staging loop. We permute the output array one more time since from $i = L - 1$ until $i = M + L - 1$ we have fully rotted the outputs arrays meaning the last device (device n) has the final output for device 1, device 1 has the output for device 2 and so on. We also prepare the final KV-cache

def pipeline(...):

...

for i in range(...):

...

outputs = jax.lax.ppermute(outputs, "pp", perm)

if len(KV_cache) > 0:

KV_cache = jnp.stack(KV_cache, axis=0)

else:

KV_cache = None

if len(KR_cache) > 0:

KR_cache = jnp.stack(KR_cache, axis=0)

else:

KR_cache = None

out_cache = (KV_cache, KR_cache)

return outputs, out_cache

We can now call this in our pipe_step method to complete our sharded forward pass.

def pipe_step(self, params, x, key, train, cache=None):

embedding_params, layer_params = params

if cache is not None:

x = x[..., -1:]

embeddings = self.embedding.apply({"params": embedding_params}, x, out=False)

layer_fn = lambda x, params, cache, key: self.block.apply(

{"params": params},

x,

cache=cache,

train=train,

rngs={"dropout": key} if train else None,

)

@partial(jax.checkpoint, policy=jax.checkpoint_policies.nothing_saveable)

def fwd_fn(state_idx, x, params, cache, key):

def grad_fn(stop_grad):

return (

lambda *args: jax.lax.stop_gradient(layer_fn(*args))

if stop_grad

else layer_fn(*args)

)

fns = [

grad_fn(stop_grad=True),

grad_fn(stop_grad=False),

]

return jax.lax.switch(

state_idx,

fns,

x,

params,

cache,

key,

)

layer_out, out_cache = self.pipeline(

fwd_fn, layer_params, embeddings, cache, key

)

logits = self.embedding.apply({"params": embedding_params}, layer_out, out=True)

return logits, out_cache

Tensor Parallelism

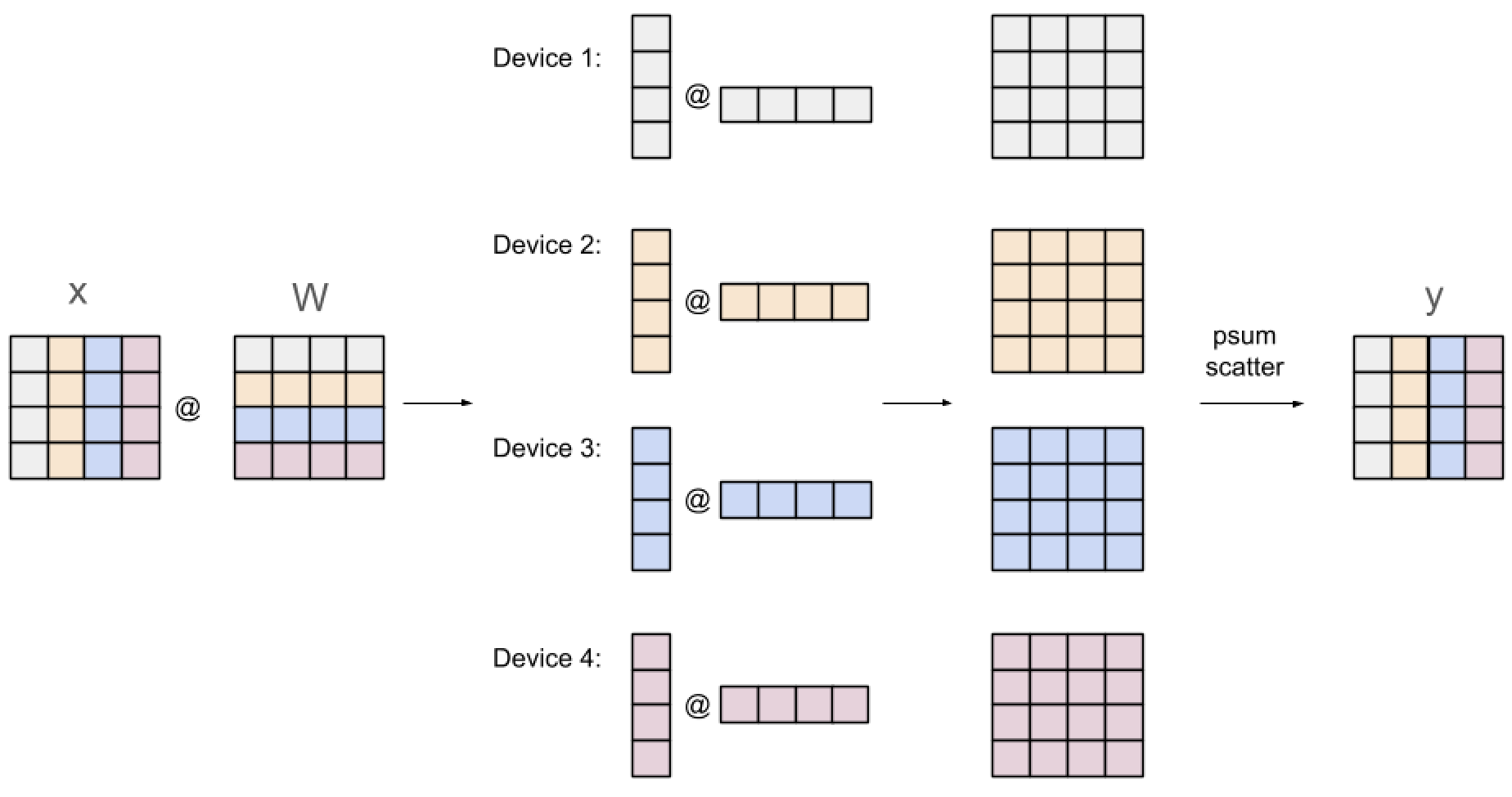

Another model parallelism (splits the model across devices instead of data) strategy is tensor parallelism. In this strategy the model is split across it’s feature dimension. An advantage of tensor parallelism is that it doesn’t face similar problems to pipeline parallelism’s bubble problems because all devices work on the same batch of data together. Tensor parallelism strongly relies on communication between different devices and is thus a popular strategy when training on TPUs due to the ICI connections between a large number of chips in a single pod (think nodes for GPUs). Suppose the model had a feature size of 512 and there were 4 devices, then there would exist 128 consecutive features across the different devices. Since the layers/modules have an intra-computation split, the devices must communicate features and outputs. There are two main strategies to do this however for our case we have chosen the scatter strategy.

The scatter strategy needs to be done for every layer. Below is the scatter strategy for the dense layer.

Suppose we are performing a matrix multiplication between $A \in \mathbb{R}^{m \times n}$ and $X \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times d}$. Using this strategy, the columns of $A$ and rows of $X$ are split across the $n$ devices, thus each device has vectors $a \in \mathbb{R}^{m \times 1}$ and $x \in \mathbb{R}^{1 \times d}$. Each device $k$, can compute $Y^k \in \mathbb{R}^{m \times d} = ax$, which contains a portion of the sum of $Y$, as $Y_{ij} = \sum_{k=1}^n Y^k_{ij}$. Hence, we need to sum the partial matrices on each device to get the final vector $y$, which can be split along the columns across the devices using the psum scatter strategy.

RMSNorm

For RMSNorm since the hidden dimension is split across devices each device first computes its local sum of squares. To get the global sum we use jax.lax.psum(..., axis_name) which performs an all-reduce so that every device receives the total $\sum_{i=1}^{n} x_i^2$. Finally, we compute the global hidden size by all-reducing each local x.shape[-1] then divide the RMS by this global dimension.

class RMSNorm(nn.Module):

model_dtype: jnp.dtype = jnp.float32

@nn.compact

def __call__(self, x: Array) -> Array:

...

rms = jnp.sum(jnp.square(x), axis=-1, keepdims=True) #local sum computation on each device

rms = jax.lax.psum(rms, axis_name="tp") # sum across devices

rms = rms / jax.lax.psum(x.shape[-1], axis_name="tp")

...

return x

Embedding

In this case, the embedding layer is also split across the devices. At the start of the forward pass, the input values are loaded as the shape $(B, \frac{T}{\text{tp size}})$ as the sequence length dimension is sharded along the TP axis. Note the idea of T being sharded is called sequence parallelism but for memory-bandwidth we begin by sharding the T dim across the tensor axis. After the embedding is applied on the inputs, their shape becomes $(B, \frac{T}{\text{tp size}}, C)$. Then, since the tensor should be split along the hidden dimension axis, the function jax.lax.all_to_all(x, axis_name, split axis, concat_axis, tiled) is applied on the inputs after the embedding layer x. The axis_name is along the tensor parallelism axis (tp), the split_axis denotes along which axis the TP sharding should occur - in this case it is the hidden dim. Since all_to_all syntax doesn’t allow for negative numbers split_axis=x.ndim-1, which is equivalent to the -1 dim. The concat_axis=x.ndim-2, or the -2 dimension which indicates that all T across the devices should be concatenated as denoted by tiled=True. Hence the final shape now becomes $(B, T, \frac{C}{\text{tp size}})$ as intended. Similarly after the self.norm is applied we do the inverse all-to-all to obtain $(B, \frac{T}{\text{tp size}}, C)$ and then use the normal weight tying to obtain $(B, \frac{T}{\text{tp size}}, V)$ . Then in the loss function, we can pmean across the tp axis since tokens on one tp axis device’s are compute with weights on another tp axis device (this will be implemented later in the main training script).

class Embedding(nn.Module):

...

def __call__(self, x: Array, out: bool = False) -> Array:

if not out:

*_, T = x.shape

x = self.embedding(x)

x = jax.lax.all_to_all(

x, "tp", split_axis=x.ndim - 1, concat_axis=x.ndim - 2, tiled=True

)

if self.is_mutable_collection("params"):

_ = self.norm(x)

else:

x = self.norm(x)

x = jax.lax.all_to_all(

x, "tp", split_axis=x.ndim - 2, concat_axis=x.ndim - 1, tiled=True

)

x = self.embedding.attend(x)

return x

RoPE

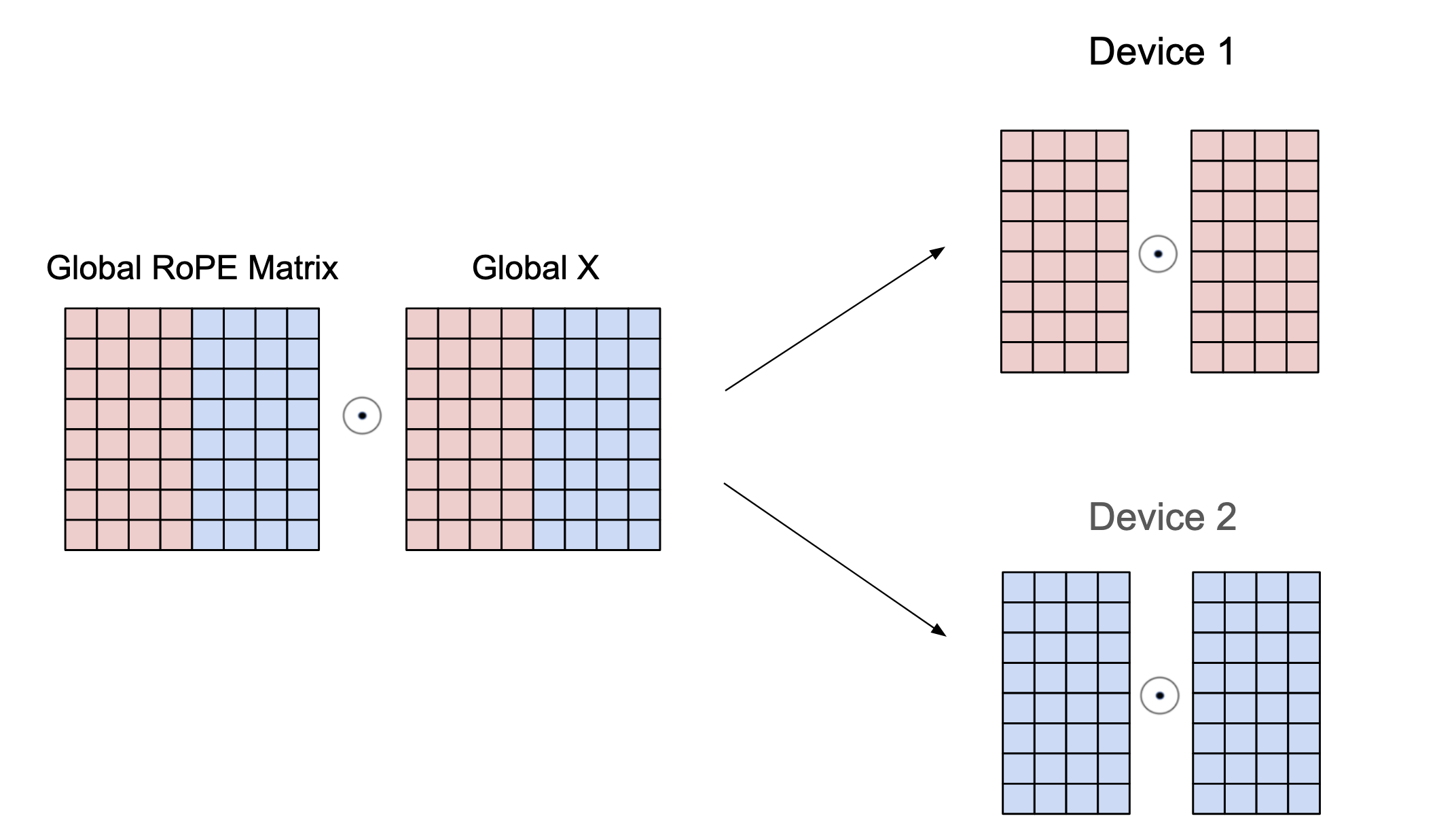

The next module that needs to change is the RoPE logic since the cos/sin matrices need to spilt for the channels that are on the device. Thus we only need to make changes in the setup method to slice the matrices. To do this, we find the current index in the tp axis and the size to find how many channels will be on each device, we call this the slice_factor. Then we use jax.lax.dynamic_slice_in_dim which is essentially arr[..., start_idx: start_idx + length but works under a jit context with dynamic values (values not known at compile time). We find the start_idx by multiplying the idx * slice_factor since that adds up the slices for the previous devices. This is done on the axis=-1 since that is the channel axis.

class RoPE(nn.Module):

...

def setup(self):

idx = jax.lax.axis_index("tp")

tensor_size = jax.lax.psum(1, axis_name="tp")

slice_factor = self.model_dim // tensor_size

self.cos = jax.lax.dynamic_slice_in_dim(

cos, slice_factor * idx, slice_factor, axis=-1

)

self.sin = jax.lax.dynamic_slice_in_dim(

sin, slice_factor * idx, slice_factor, axis=-1

)

Attention

When applying tensor parallelism to MLA, we have to consider how sharding will work when performing scaled-dot product attention. The easiest approach is to shard the heads along the tensor axis since they are independent of each other when performing the attention operation. After splitting the local q,k,v across heads, the current interpretation is that for all heads we have a fraction of the keys, queries and values (split across tp). Thus we can perform an all-to-all to accumulate all the qkv across all heads and then split the heads across the tp axis.

class MLA(nn.Module):

...

@nn.compact

def __call__(

self,

x: Array,

*,

KV_cache: Optional[Array] = None,

KR_cache: Optional[Array] = None,

train=True,

) -> Tuple[Array, Tuple[Optional[Array], Optional[Array]]]:

...

q, k, v = jax.tree.map(

lambda x: rearrange(x, "B T (nh d) -> B nh T d", nh=self.n_heads),

(q, k, v)

)

q, k, v = jax.tree.map(

lambda x: jax.lax.all_to_all(

x, "tp", split_axis=1, concat_axis=3, tiled=True

),

(q, k, v),

)

...

We can then perform attention as normally applied. Then we want the output to be sharded across the channels of output so we first regather all heads and spilt back the output along the channels. Then we are able to reshape to concat the heads with the dimension as normal.

class MLA(nn.Module):

...

@nn.compact

def __call__(

self,

x: Array,

*,

KV_cache: Optional[Array] = None,

KR_cache: Optional[Array] = None,

train=True,

) -> Tuple[Array, Tuple[Optional[Array], Optional[Array]]]:

...

output = scaledDotProd(q, k, v, mask)

output = jax.lax.all_to_all(

output, "tp", split_axis=3, concat_axis=1, tiled=True

)

output = rearrange(output, "B nh T dk -> B T (nh dk)")

output = Dense(features=self.model_dimension, dtype=self.model_dtype(output)

output = nn.Dropout(rate=self.dropout)(output, deterministic=not train)

return output, (KV_cache, KR_cache)

We now define the rules for the partition spec since certain features need to sharded along another axis as well. We shard the RMSNorm params in both the embedding and layer blocks. We shard the first axis of the the kernels (first axis ignoring pipeline since that will get split) in all Dense blocks in the layer as well, otherwise for biases the sharding is only for the pipeline dim.

class shardedModel:

...

@staticmethod

def get_p_spec(

model: Tuple[Embedding, Block], mesh: jax.sharding.Mesh, config: modelConfig

) -> Tuple[jax.sharding.NamedSharding, jax.sharding.NamedSharding]:

...

def layer_partition(key: Tuple[str, ...], x: Array) -> P:

path = join_fn(key)

if "gamma" in path or "beta" in path:

return P("pp", None, None, "tp")

if x.ndim == 3:

return P("pp", "tp", "dp")

return P("pp", None)

def embedding_partition(key: Tuple[str, ...], x: Array) -> P:

path = join_fn(key)

if "gamma" in path or "beta" in path:

return P(None, None, "tp")

return P(*(None for _ in range(x.ndim)))

Combining these all together we have a strategy for 3-D parallelism. Note that each of these strategies can be further improved and may be explored in the future. For example, better pipelining algorithms exist such as 1F1B or DualPipe which seek to reduce the bubble time while maintaining better FLOPs. For Tensor Parallelism, we can explore gather strategies that allow for async communication operations. However, the process of integrating these advanced strategies into n-D from scratch in JAX is very similar to how we have done it here. We will now look at the configs and main training loop used to run the model.